Gradually TypeScript: Adding types to React components without removing their propTypes.

This is part of a series on gradual TypeScript migration. You can find a list of all the posts in the series here.

In short: As you migrate your codebase to TypeScript, it might make sense to have both PropTypes and TypeScript types available for your React components. This section gives an example of the best pattern I’ve found for doing this so far.

Migrating to TypeScript is a lot of fun because it means I get to run in to all the weird edge cases I could ever want. It isn’t always the edge cases that turn out to be fun though; some things that seem pretty straightforward onpaper have turned out to be pretty weird as well. For example, using PropTypes and TypeScript types simultaneously can very much be a bad time.

Before I go into why this is the case, it might help to explain why you would want both TypeScript types and PropTypes at the same time in the first place.

# Setting the stage.

When you think about writing React components in TypeScript, one of the most obvious wins is the ability to stop thinking about PropTypes. As a quick refresher, PropTypes are weak runtime guarantees that your props are the right type. Here’s a component for illustration purposes:

const propTypes = {

target: PropTypes.string,

};

function Howdy(props) {

return (

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/" target={props.target}>

Howdy

</a>

);

}

Howdy.propTypes = propTypes;Whenever I put <Howdy />, React would render this HTML:

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/">Howdy</a>If I do something like <Howdy target="_blank" />, React would spit out:

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/" target="_blank">Howdy</a>And of course, if I tried to do something disastrous like

<Howdy target={2} />, I’ll get an error like this in my browser’s console at

runtime:

Warning: Failed prop type: Invalid prop `target` of type `number` supplied to

`Howdy`, expected `string`.Love to see that. However, it would be great if we could get these warnings well before they make their way to the browser, wouldn’t it? That’s pretty much exactly what TypeScript is for. Here’s that same component in TypeScript:

function Howdy(props: { target?: string }) {

return (

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/" target={props.target}>

Howdy

</a>

);

}That’s it! If we ever tried to do something like <Howdy name={2} />,

TypeScript would catch it and yell at us in a similarly mean manner, all before

our code even runs.

# Here comes the problem.

If you have to migrate a large codebase all at once, it’s a safe bet to do so grdually. TypeScript isn’t an all-or-nothing adoption — you get benefits proportional to how much of your codebase adopts it.

In addition to migrating gradually, it makes sense to enable some of

TypeScript’s stricter options. This includes enabling

strict null checks,

which means that if something is supposed to be a string, it is not allowed to

also be null. Why go through the effort of changing your programming language

if you’re not gonna take full advantage of it?

Finally, typechecking stops at the barrier between TypeScript and JavaScript. TypeScript can make sure everything in your .tsx React components are squeaky clean, but you are welcome to ignore pretty much every single type once you use that component in a regular .jsx file.

Putting these things together, I needed to take a regular React component and turn it into something pretty well typed. I also needed that same component to still have some guarantees that it’s being used correctly outside of TypeScript.

# Trying out PropTypes.InferProps

If you want to use the PropTypes library in a TypeScript file, you need types for the library. We’ll also probably want some types for React as well. I got those both from DefinitelyTyped, which hosts a bunch of types for untyped NPM projects. Installing them is as easy as you’d expect:

yarn add @types/prop-types @types/reactAs

this wonderful post

points out, the types in this package comes with a fun feature:

PropTypes.InferProps. It’s a type that can turn the type of your PropTypes

object into a normal-looking TypeScript type. An example might make more

sense:

const propTypes = {

target: PropTypes.string,

};

type Props = PropTypes.InferProps<typeof propTypes>;

// type Props ≈ { target: string | null | undefined }Brilliant! All I have to do now is just insert PropTypes.InferProps into all

of my components and th—

const propTypes = {

target: PropTypes.string,

};

type Props = PropTypes.InferProps<typeof propTypes>;

function Howdy(props: Props) {

return (

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/" target={props.target}>

{/* ~~~~~~~~~~~~

* ERROR:

* Type 'string | null | undefined' is not assignable to type 'string | undefined'.

* Type 'null' is not assignable to type 'string | undefined'.

*/}

Howdy

</a>

);

}

Howdy.propTypes = propTypes;Ah heck, we have a type error. We seem to have done everything right, though. What went wrong?

It looks like PropTypes.string validates that a prop is a string or that

it’s null or undefined. Here’s

an excerpt

from @types/prop-types where that’s defined:

export interface Requireable<T> extends Validator<T | undefined | null> {

isRequired: Validator<NonNullable<T>>;

}

export const string: Requireable<string>;This definition makes sense if you think about it: if a PropType isn’t marked as

required, it is allowed to be null or undefined. React doesn’t seem to care

about the difference between null and undefined either.

<Howdy name={null} /> happily spits this out:

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/">Howdy</a>So if PropTypes.InferProps sees PropTypes.string, it’s fair game for it to

turn that into string | null | undefined, since those are all types that

PropTypes.string would be cool with. If the types for PropTypes don’t seem to

be misbehaving, that means that React’s types might be. What’s the type for an

anchor tag anyways?

I’m glad you asked:

interface AnchorHTMLAttributes<T> extends HTMLAttributes<T> {

download?: any;

href?: string;

hrefLang?: string;

media?: string;

ping?: string;

rel?: string;

target?: string;

type?: string;

referrerPolicy?: HTMLAttributeReferrerPolicy;

}It looks like all of the properties on this type are optional. To TypeScript,

this means that they’re either there, or they’re undefined. If we define

target at all, it better be a string or literally undefined.

While this makes practical sense, it omits null as a valid option unless we turn

off strict null checks (and I’m not doing that). The result is that our target

value (string | undefined | null) can’t fit into the anchor tag’s target

prop (string | undefined).

What can we do about this? Well, we could do the dumbest thing first and just

check to see if props.target is null:

const propTypes = {

target: PropTypes.string,

};

type Props = PropTypes.InferProps<typeof propTypes>;

function Howdy(props: Props) {

const target = props.target === null ? undefined : props.target;

return (

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/" target={target}>

Howdy

</a>

);

}

Howdy.propTypes = propTypes;This isn’t a good look. It’s a lot of extra logic that we’d need to do for most of our props in most of our components.

We could do slightly better than that, however. TypeScript gives us a super slick Non-Null Assertion Operator™ to tell it when we are positive something isn’t ever going to be null:

const propTypes = {

target: PropTypes.string,

};

type Props = PropTypes.InferProps<typeof propTypes>;

function Howdy(props: Props) {

return (

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/" target={props.target!}>

{/* This thing riiiiight here ^ */}

Howdy

</a>

);

}

Howdy.propTypes = propTypes;That ! says “This thing? It’ll never be null, promise”. We can’t actually make

that promise, though, because props.target totally could be null, and all of

this would totally work as expected if it were. Plus, it’s usually good practice

to lint against the non-null assertion operator since it tends to be a sign of

other problems.

So what’s that leave us with?

# The actual solution we went with.

const propTypes = {

target: PropTypes.string,

};

interface Props {

target: string;

}

function Howdy(props: Props) {

return (

<a href="https://kwi.li/coo'/" target={props.target!}>

Howdy

</a>

);

}

Howdy.propTypes = propTypes;Nothing fancy or clever, unfortunately; just good ol’ fashioned repetition.

It’s obviously not perfect. I have to define my props twice, and I have to keep them in sync with each other, and none of that is all that slick. However:

- I don’t have to worry about edge cases. I’m sure there’s a custom proptype

somewhere in this codebase that wouldn’t work with

InferProps. - I don’t have to disable strict mode and I don’t have to use

!anywhere. (Did I mention that we lint against those?) - It’s straight-forward and easily understood by engineers looking for TypeScript examples.

- Because of how expressive TypeScript is, my TypeScript types can be more accurate than my existing PropTypes.

- Once we’re at a place where all (uh, probably most) of our React components are written in TypeScript, we can just delete the PropTypes object and call it a day.

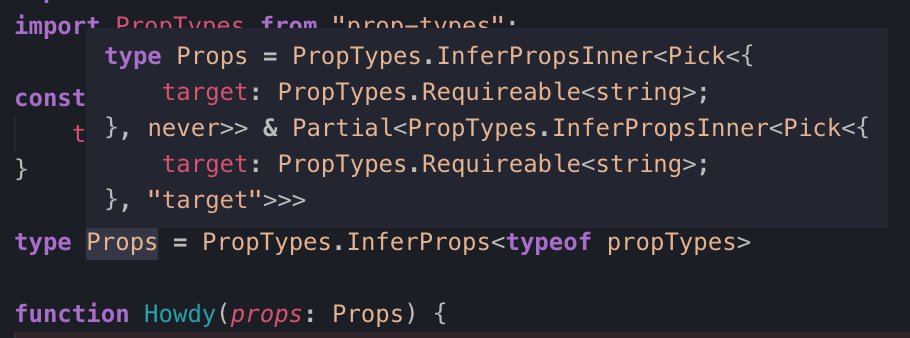

# Anyways,

I can’t really speak to why the React types look like this, but I’m sure there’s

a good reason. (If you know, please tell me!) The most finicky part about this

migration has turned out to be figuring out patterns that will be understandable

to people who don’t have a ton of experience with TypeScript. I think that even

if PropTypes.InferProps did work perfectly out of the bag, it would take a lot

of time for other engineers to wrap their heads around it. I don’t think anyone

would look at what it spits out and be able to understand it:

If you want to play with a reproduction of this type mismatch, check out this code sandbox that reproduces the problem. I’ve reported this mismatch as a problem on Definitely Typed, but I’m still waiting on a response. If you come up with a slicker solution than I have, I would love to hear about it.